The World Frank Walter Made

This essay is excerpted from By Land, Air, Home, and Sea: The World of Frank Walter, out this month from David Zwirner Books and edited by Hilton Als. Occasioned by an exhibition of Walter’s paintings that Als curated in 2022, the book examines the life and legacies of a remarkable artist who toiled in obscurity before his death in 2009—and his subsequent “discovery” as a major figure, by the art world’s cognoscenti, after a small portion of his vast body of work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2017. This essay examines a formative period in the life of an artist who was born and spent most of life on the small Caribbean island of Antigua—but who decamped in 1961 to live and work, in solitude, in the lush forests of the nearby island of Dominica.

— The Editors

To reach the Ding-a-Ding Nook—a place in Antigua that appears on no map, but whose name has long fed the historical imagination of this small and arid island in the Leeward Antilles—you leave the Caribbean capital where Frank Walter was born, and head south. You roll through sunbaked hills dotted with prim concrete homes and the crumbling remnants of a sugar trade that was, for centuries, Antigua’s lifeblood and its curse. You pass hamlets whose names—Piccadilly, Piggotts, English Harbour—underscore that the island’s 108 square miles were owned, from 1632 clear until 1981, by England’s kings. And then, after a half hour’s drive and in the parish of Saint Paul’s, you reach the first village the English founded here. From the sleepy jetty in Falmouth, it’s a hot mile’s walk along a rocky track lined by cacti and scrub to a beautiful, empty beach. Its chalk-white sand and turquoise water belong in an internet ad touting Antigua’s “365 beaches (one for each day of the year!)” to tourists, who are the island’s lifeblood now. Here, or on a hill nearby at any rate, the legend of the Ding-a-Ding Nook was born.

It began, as the story goes, on a moonlit night not long after Antigua’s first English governor, Edward Warner, arrived from nearby Saint Kitts, where his father, Sir Thomas Warner, had founded an English colony in 1626. Six years later, the son built a house near Falmouth for his wife and children. But late one night while he was away, his wife heard a worrying noise. Mrs. Warner opened a window and looked down toward the beach. Long canoes, carved from tall trees on an island more forested than this one, were sliding ashore. From their sides leapt a party of Caribs—members of the Indigenous group for whom the Caribbean is named, and many of whose descendants now call themselves Kalinago, for the word in their language meaning “human being.”

The Caribs’ forebears had left the South American mainland a few centuries before. They’d worked their way up the Antillean chain, often forcing out the islands’ previous inhabitants. The Caribs were not, in the 1630s, maintaining a steady presence on Antigua—this dusty island had nothing on the lush mountains of their main redoubt, 120 miles to the south. Dominica, as that island was named by Christopher Columbus (he happened to sail past it on a Sunday), was known to them as Waitukubuli, meaning “tall is her body.” But the Caribs had grown wary of the claims of the English on the Leeward Islands. And upon landing in Antigua that night, they surrounded the governor’s house, then bound Mrs. Warner and her children with cords. And then—after swinging one child’s head against a rock—they made off in their canoes toward the south.

Edward Warner returned home the next morning to find a child dead and his family gone. He gathered a boatful of men with guns and sailed south toward the Caribs’ home base in Dominica. He alighted on the steep green shores of an island often ringed, thanks to trade winds, by rain clouds. Warner confronted his wife’s captors. He eventually managed, with the help of his guns, to get her back. But afterwards he wasn’t convinced that her honor was intact. Overcome with jealousy, he did not welcome his wife back into their marital home in Antigua. Instead, he installed her in a walled “keep” down the shore, which he dubbed the Ding-a-Ding Nook.

The misery to which poor Mrs. Warner was subjected did not lessen the hostilities between her husband’s dysfunctional clan and the Indigenous people with whom the Warners were entangled in numerous ways. For if Edward Warner’s wife did lie with a Carib, she wasn’t his only kin to do so. His father, Sir Thomas, had fathered a son with a Carib woman. “Indian Warner,” as Edward’s half brother was known, managed to become a leader of his mother’s people in Dominica, before a third brother, Philip Warner, traveled there a few years later to summon him to a fallacious peace summit. Philip Warner shot Indian Warner dead. In those days, while killing “Indians” was not considered a crime by the English Crown, killing one’s brother was, and Philip Warner, convicted of fratricide, was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

The jail in Antigua where Philip Warner’s sister-in-law lived out her days wasn’t built of the same lasting stuff as the Tower of London. But its memorable name endured to be attached to a cave by a beach near to where Frank Walter—centuries later on a hilltop outside Falmouth— forged his mammoth oeuvre. It’s hard to say when and how exactly Walter seized on this story to the degree that he declared himself the Seventh Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies and the Ding-a-Ding Nook. But Walter—who would have his own formative run-ins with the wild island of Dominica, and who was obsessed with the oft-occluded racial mixing that typifies many family trees in the Caribbean—seized on it indeed.

*

The island of Antigua, where Frank Walter grew up, was indelibly shaped, as was he, by the sheer and bloody fact of Antigua’s having been owned by the English for 350 years. Its Spanish name may have come from Columbus, who sailed past in 1493 and named the island’s scrubby peaks for a cathedral in Seville, but no European who perused its harbors saw fit to set up shop in a lasting way until Edward Warner in 1632. While nearby islands—Saint Lucia, Dominica, Trinidad—were swapped multiple times among the English, French, and Spanish colonial powers, Antigua was only ever held by the English, who brought the industry that long defined the region: Big Sugar.

This business that brought millions of enslaved Africans to the Americas to process sugarcane on an industrial scale was first “perfected” in Portuguese Brazil. An Englishman, James Drax, brought a boatload of giant rollers and copper pots from there to Barbados in the 1640s. In so doing, he transformed that English island from a struggling colony of tobacco farmers into a sugar juggernaut. A few decades later, Drax’s cousin Christopher Codrington founded a plantation on Antigua that became the first locus of an industry that by the mid-1700s would blanket the island with over a hundred such estates, brutally minting English fortunes from sucrose. And it was Codrington’s activities as the planter and potentate who leased Antigua’s sister island of Barbuda from the Crown in toto that most shaped this seat of British naval power in the Leeward Islands, which Horatio Nelson, after visiting in 1784, called “a dreadful hole.”

By the time Francis Archibald Wentworth Walter was born in 1926, Antigua’s sugar trade was a century into its long decline. After slavery’s abolition in the 1830s, some plantations closed. Others didn’t, and their Black workers’ lives differed little from those of previous generations. It wasn’t until the 1960s, with the rise of cheap travel, that tourism became Antigua’s main industry. In 1948, Frank Walter, a star graduate of the Antigua Grammar School, made history as the first Black man to become a manager, at the age of just twenty-two, in the Antigua Sugar Syndicate. This jumping of the color bar signaled the slow but growing movement among Black Antiguans, who comprised nine-tenths of the populace, toward self-rule. However, the position Walter won in the island’s agricultural economy and its vexed racial hierarchy also fed his keen interest in his European forebears, from whom he got his surname, as opposed to his kin with African roots, far more numerous, who gave him his complexion.

To the outsider steeped in contemporary efforts to confront Eurocentric biases, Walter’s affinities, in this regard, may seem strange. But the riddle of identity has long been tricky in the Caribbean. On islands whose native peoples were largely killed off and that are now populated by the descendants of enslaved Africans and crooks and outcasts from elsewhere, the search for “roots”—for a grounded sense of identity and home—has traced many routes. In some places, the descendants of both colonists and the enslaved embrace their islands’ Indigenous pasts. The overwhelmingly Iberian and African populace of the once Spanish island of Puerto Rico has made the language and lore of its native Taíno (“Boricua!”) key to Puerto Rican-ness now. The Rastafarians of Jamaica voice ties to an African emperor in a far-off land—Ethiopia—that’s as distant from their forebears’ own as Jamaica is from the Arctic. Walter’s tack was different from these. But he was by no means the only Caribbean person of African descent to have nurtured, as a path to a proud sense of self, a deep interest in courtly circumstance and European gentry. The best known in a long line of such figures is Henri Christophe of Haiti, who built his magnificent Sans-Souci Palace in the early 1800s. Upon declaring himself king of a new Black nation, Christophe did not gild his court with the icons of his Bambara and Igbo ancestors. Instead, he based his claims to peerage and power in a new nobility while designing his own coat of arms according to customs of heraldry from France. Haiti’s Roi Christophe was the first, but—on these islands shaped for five centuries by the mores and ideas of Europe—he would not be the last. Walter’s own interest in noble airs was, by his own account, stirred by his grandmother’s tales of how his ancestors had descended “in patience and resignation from the grandest mansions and bluffs in Antigua” to homes like the humble house in Saint John’s where she raised him.

*

Walter’s grandmother did not tell him what recent scholarship has revealed: that a preponderance of the enslaved Africans who disembarked at Saint John’s docks came from the Bight of Biafra, on the Gulf of Guinea along Ghana’s so-called Gold Coast. Significant numbers also arrived from ports in places such as Senegambia and Sierra Leone. These facts aren’t taught in Antigua’s still deeply British schools. As in much of the West Indies, traces of African cultures—for example, the popular mancala-like board game known as warri—are passed on informally, as oral lore and in folk rhymes invoking, say, the Ashanti roots of many Antiguan people (“Shanti-shanti, go put on panty!”). If such tales featured in Walter’s youth, he was much more drawn to the side of the family he could research in books: the owners of the island whose lineage and deeds were recorded in the kind of written records that Walter, as a scholar and a “true Anglo Saxon,” revered.

He especially loved recounting the life story of his forebear John Jacob Walter, an enterprising German who left the Rhineland in the 1700s and initially worked in Antigua as a baker. After winning a lucrative contract to supply bread to the Royal Navy, John Jacob Walter turned his profits into estates. He would bequeath the Walter surname to eleven children born to the mulatresse with whom he partnered in Antigua, and to those children’s future progeny, both enslaved and free. That part of Frank Walter’s line was plain. More creative were the ties he conjured, reaching back centuries, to King Charles II. Frank Walter called the king “Charles Francis Walter” and claimed that, before his restoration to England’s throne in 1660, he founded a secret Royalist refuge in Antigua for European nobles in exile. (Walter also wrote that while Charles was on this unrecorded trip to the tropics, he grew as “sable” in hue as Walter.)

The Antiguan-born writer Jamaica Kincaid, who grew up in Saint John’s in the 1950s, attended a primary school named to embody all that she loathed about the island’s colonial legacy. In A Small Place (1988), she writes bitterly of being taught to revere a minor royal whose ballyhooed visit to Antigua to dedicate the Princess Margaret School was occasioned by the banal fact that, back in England, the love life of this “putty-faced princess” was a mess. Frank Walter felt differently: he spent those years telling anyone who would listen that he was a suitor far more eligible by pedigree to wed poor Margaret than was the Earl of Snowdon. When, in 1953, Walter left Antigua to tour Europe with the nominal aim of gaining the knowledge he needed to modernize Antigua’s sugar trade, his trip’s deeper import was seeing in person the castles and storied dales that shaped his sense of himself. Despite the poverty and prejudice he experienced, “the closer I got to Europe,” he said, “the less strange I began to feel.”

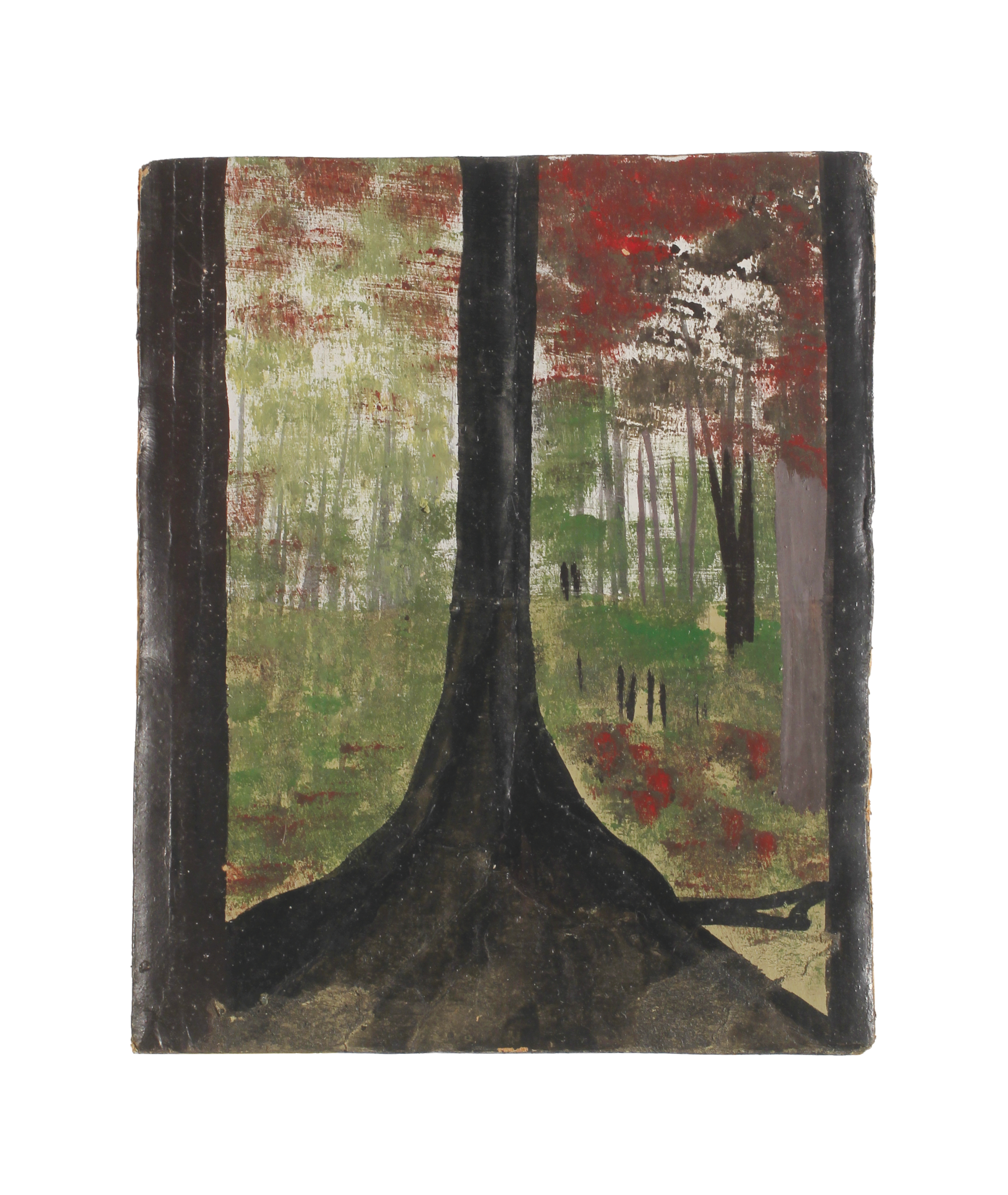

Walter spent nearly eight years wandering the continent. Decades later, he would still be committing his memories of its northern light— Scotland’s heather, Bavaria’s gray but glowing peaks, “the multi-colored illumination of the vast Lombardian valley”—onto cardboard with paint. Walter’s vast corpus includes thousands of pieces that refract the sun-soaked vistas of the Caribbean. No small part of his power as a painter of place derives from his will to capture the genius loci of the varied landscapes he absorbed by articulating, in shades muted or bright, their echoes with each other. Europe proved vital to Walter’s larger journey toward self-making. But it was on the island of Dominica, where he first settled upon returning to the Caribbean in 1961, that he became the artist whose endeavors still resonate, as I found on a recent visit to “the nature island,” where he realized an outsized vision of a landscape he also shaped.

*

“You know, this is the only place in the West Indies,” a friend says soon after I land in Dominica, “where every day, the sun shines through raindrops.” He was right, on that drizzly but rainbow-bright August afternoon. And he’s been right on every day I’ve had the good fortune to spend on the island to which Walter moved in 1961 to realize a more personal vision of “industrial development.” He’d been informed, about his return to the Caribbean, that his ideas for modernizing its agribusiness were no longer needed. So he boarded a steamer for Dominica and disembarked at Portsmouth, an old banana port in the north where he had cousins. There, on twenty-eight acres of Crown land he had won permission to develop, he set out to turn an elevated patch of Dominica’s jungle into the project he called Mount Olympus.

There is a reason Dominica is called “the nature island.” Whereas Antigua touts a beach for each day of the year, the analogous line in Dominica hails 365 rivers tumbling down from mist-shrouded peaks onto rocky shores. Dominica’s forbidding heights allowed it to remain an Indigenous holdout. Today it is the only island in the Antilles with a visible Indigenous community—its members maintain a Kalinago Territory along the windswept Atlantic coast. Portsmouth, on the island’s calmer Caribbean side, is a sleepy place. Its main street’s most happening spot is a café, Miss Olive’s Shop, named for the “huckster” on whose steamer Walter arrived here. At Miss Olive’s Shop, taxi drivers breakfast on saltfish and coffee, by a parking lot where windshields are adorned with oblique, often pious phrases—REDEMPTION, NEVER THIRSTY, JESUS DID IT AGAIN. Later in the day, the taxi drivers’ vans will convey passengers along treacherous roads through Dominica’s bush, to the island’s capital and elsewhere.

There aren’t many people here who recall Frank Walter: it’s been more than half a century since he abandoned his Mount Olympus project. But one person who does remember his doings is a gentle farmer and musician who, in the Rasta way, doesn’t go by his “government name” but rather by a moniker, I-Noah, that rejects slavery’s scars. I-Noah is very happy to explain his familial ties to “Uncle Frank” and to share his memories of a man whose plot of avocado trees I-Noah has tended since he returned from a European sojourn of his own that lasted, he says, “seven years, six months, twenty-two days.”

The length of I-Noah’s time away and his oddly precise diction are not his only traits that recall the great-uncle with whom he deeply identifies. He tells me this when I find him at the spot where he’s waiting for the World Bank to build a new cinder-block house to replace the one he lost in Hurricane Maria in 2017. He tells me how it was his talent as a calypso singer that brought him to Europe in the 1990s, and that he enjoyed living in France and touring the continent. But once he and his girlfriend-manager fell out (“when you make nice music,” he explains, “women does flock so”), he came home with the plan of “living natural” and feeding himself from the rich patch of sod that had been in his family for generations. Its bounteous avocado trees, he says, were planted by his Uncle Frank. I-Noah has memories from boyhood, he says, of Uncle Frank making him toy cars from sardine cans, and of Uncle Frank tromping up the mountain to where he felled the same towering gommier trees the Caribs had once turned into canoes, but which his Uncle Frank processed into charcoal. Others older than him, I-Noah says, will recall more.

We find a cane-wielding gent who gives his name as Webster Brody but says that everyone calls him Ti Baby. He recalls that no one could understand, when he was a boy, how one man produced the thirty bags of charcoal that Walter brought each week to market on a tricycle. “But Mister Walter was a mysterious man,” Ti Baby muses, mysteriously. “He did carry a small red book.” A man with glaucous eyes and gray dreadlocks whom people call Lepo then speculates, recalling Walter’s aspect, about the source of his power: “Him was a serious man. Him no skin teeth.” (He wasn’t, that is, given to grinning.) The most expansive account comes from Mico, or King Mico, as I-Noah calls him on account of the nineteen times he has been crowned calypso king of Dominica’s north. King Mico says that “Mister was a mystic man. An inventor and a scientist. An architect.” King Mico is sitting in his one-room home surrounded by drying piles of herbs. He fixes me with a sage glare. “Mister did turn his mental power on the mountain, into physical.” Behind him on a shelf, next to bottles of ginger wine, sits a plastic-jeweled crown. He wants to be sure I understand what Walter, beyond the feats of his productivity, drew from his time there. What he says—“Mister did build his self on the mountain, where nature met him in fullness”—echoes Walter’s own writings on how, in the jungle, his industry fed his art. “Light and Shadows became my best companions,” Walter noted. When not working under the moon or making carvings, he often slept in the jungle on a crocus bag. As he was moving kilns and cutting trees,

The wind became my lover, as it caressed me and tickled me and rejuvenated me to this productive task, and the sunlight fed me, with its direct lunch of mid-day rays, as more often aiding the wind the persistent raindrops kissed my cheeks, to cool me beyond my desire. Even so I would chop the faster.... It was an enriching Coventry, and a Hermit’s Exile, I was brought closer and closer to contact with God and Nature in this divine stillness.

In the stillness of morning time, I meet I-Noah and a man called Roland to trek up a dirt track that leads, after a sweaty forty minutes, to a vine-choked clearing. The edge of what was once Walter’s acreage is now adorned, as are many patches of high ground the world over, with a cell phone tower. The view, of the whole of the bay at Portsmouth and the Cabrits promontory beyond, is magnificent. Roland has tended a nearby plot of dasheen for decades, and he points into the bush with his cutlass, to where Walter’s trolleys ran on wooden tracks he built himself, from his coalpits down to where he’d load his tricycle for market. “All down this everlasting hill,” Roland says, “Mister rolled it so.” Walter’s tracks would have been lubricated with the thick green slime that is won, Roland demonstrates, from crushing leaves between one’s fingers.

The regrown forest is too thick to fight through with a single cutlass. But we’re able to hike around, another way, to the parcel’s bottom. There, by a burbling stream that lines the lower edge of Walter’s old domain, we stand among the smooth legs of Bwa Mang trees. Crabs scuttle along the trees’ slablike roots as an army of frogs croaks under dripping limbs. It isn’t hard to understand why Walter described this as the place where he “discovered that nature had its own language,” or that it convinced him that building “a suitable domicile for the development of Industry, Philosophy and Art is no tremendous Utopian Dream.”

When, in 1965, Walter took a well-earned break from his labors to return briefly to England, his main aim was to acquire steel tracks and carts to replace his wooden ones. I-Noah pulls out his phone to play us a recording of his uncle describing, in what Walter called his “Oxford Heidelberg accent,” how he was denied entry at Southampton by officials who cared not a jot about the equipment he needed but were bemused by this sable-skinned colonial’s insistence that he was a blood relative of the Duke of Bedford. “They were afraid,” says I-Noah to Roland’s nods, “of his power.”

Two years later, Dominica’s government offered Walter $50,000 to return to their domain the acreage he had cleared for planting. He’d hear none of it. He said the labor he poured into his Mount Olympus Industrial and Agricultural Estate was priceless, and he’d been speaking with a Canadian maker of stereo equipment who was keen to buy his charcoal. His ensuing departure for Antigua, when it grew clear that the government would not grant him the title, was bitter. But back in Saint John’s, behind a photography shop there, after eight years of absorbing Europe’s sights and six more with Dominica’s murmuring trees, he turned in earnest to the artistic practice that would lead him, ultimately, to the hilltop over Falmouth where he found the “peace tranquility” he required.

In poverty, Frank Walter created the kind of life that, in its wholesale devotion to making work, many artists fantasize about having but few ever realize. Not the least of his triumphs was that he managed to do this on the thirsty island where he grew up. It was on Antigua, on the hill by the Ding-a-Ding Nook, that Walter became the mighty artist he was meant to be. But the place where he proved he could do so, to himself and to his people, was the lush island of Dominica, where he didn’t just scale Mount Olympus but built it. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast