KANAVAL

Fat Tuesday, across the Americas and around the world, goes by many names—mardi gras, mas’, carnival, kanaval. These festivities, which herald the impending start of Lent, comprise a “farewell to the flesh” with roots in Europe: in Catholic tradition, Lent is a time to forgo meat and other pleasures for the 40 days between Ash Wednesday and Easter. Today in Venice and Rome, masked believers still mark Lent’s eve with drunken fetes. But it was in the old slave ports of the so-called New World, across the Atlantic, that carnival found its greatest modern forms. Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, some ten million enslaved Africans were brought across the sea to grow sugar and coffee for distant tables. And from New Orleans to Trinidad to Barranquilla and Brazil, carnival became a time for enslaved people to engage in “turnabout” and play—to dress up and ridicule their masters; to honor their ancestors; to enact, with the help of characters drawn from history and myth, epic dramas in the street. All of these places, when it comes to carnival arts, have their own amazing traditions. But there’s a unique power and beauty to the forms carnival has taken in Haiti, the only American nation founded by its enslaved.

For the past 25 years, Leah Gordon has been documenting what Haitians call kanaval, in the beautiful city of Jacmel on Haiti’s south coast. Gordon is a British-born photographer, artist, and curator who has devoted much of her career to “re-presenting” the riches of contemporary Haitian art, and bringing due attention to its leading exponents. In 2018, Gordon served as co-curator of the acclaimed Pioneer Works exhibition PÒTOPRENS: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince (and as co-editor of its acclaimed accompanying book). Last year, she returned to Jacmel to create a film, with her co-director Eddie Hutton-Mills, that gives cinematic form to the madigra traditions she first documented in KANAVAL, her seminal book of photographs of Jacmel carnival’s leading characters and troupes.

The film KANAVAL: A People’s History of Haiti in Six Chapters, which is currently on the festival circuit, shows how Jacmel’s artisans recount the proud triumph of Haiti’s revolution, in 1804, and the trials Haitians have weathered since. To coincide with the film’s release, Gordon and HERE Press have published a new and expanded edition of its namesake book, whose photographs are accompanied by oral histories from Gordon’s subjects (who she insists on paying, contrary to the old norms of documentary photography, to collaborate in these images’ creation). We’re honored, this Mardi Gras day, to share a potent glimpse of “people taking history into their own hands” as Gordon puts it, “and moulding it into whatever they decide.”

- Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Chaloska (Charles Oscar)

In 1912, Chief Charles Oscar Étienne was the military commandant in charge of the police in Jacmel. He was tall and strong with big feet, big teeth. Everyone was afraid of him. At that time there was political instability in Port-au-Prince. President Sam had just been assassinated, and Charles Oscar took his chance to take five hundred prisoners from the local jail. He killed them all. There was so much blood it made a river of death. The people were so angry that they rose up and tore the police chief to pieces in the street and burnt him up. He was killed in the same violent way that he’d treated the people. This story has always been very striking to me, and in 1962 I decided to create the character of Chaloska for Carnival. I designed the military uniform and made the big false teeth with bull’s teeth bought from the market.

When I created Chaloska I also wanted to create some other characters to go along with him, and I came up with Mèt Richa and Doktè Kalipso. Mèt Richa is a rich lawyer with a big bag full of money and a big fat stomach. He walks with the Chaloska troupe buying justice and bribing the judges. He represents the impunity and corruption that hides behind Chaloska, and he is the real chief of the city. Doktè Kalipso is an old hunchbacked doctor in a suit with a stick in his hand. He works for Chaloska and checks on the health of the prisoners, always reporting that they’re healthy when they’re dying.

These characters are still here in Haitian society, so it’s good to parade them in the streets. It’s a message to all future Oscars that they will end up this way. The troupe goes to different places in town, threatening the people. The boss Chaloska always dies in the end, and the others call for mercy because they’re cowards. But then another Chaloska straightaway replaces him. This is to show the infinite replication of Chaloskas, which continues to produce the same system. There will be Chaloskas until the end of the world. They began at the beginning, and will not end until the end.

- Eugène Lamour aka Boss Cota (2002)

Madamn Lasiren (Madame Mermaid)

Madanm Lasirèn is a Vodou spirit who lives under the sea and does mystical work there. When I walk the streets I sing her song: Mwen Lasirèn, mwen rele anmwe, lè mwen mache nannwit, male rive m (‘I am Lasirèn, I cry out, when I work mystically by night, misfortune may befall me’). Because she’s a fish she has to disguise herself as a woman to be at Madigra. A mask and hat cover her fish’s head, and the dress she wears covers her fish’s tail. The chain she wears is a sacred chain, a fetish called Manbo Byen Venu (‘Vodou Priestess Welcome’). She also wears gloves, and carries an umbrella, and a baby, her child, who is called Marie Rose. Each year I change the disguise and fashion a new baby. In order to get inspiration I go to the place where the big beasts live, and they instruct me how to do Madigra.

I dream of Lasirèn all the time. I love and honour her. That is why I chose her—because my grandmother, father and mother all served the spirits. I’ve been doing her now for eighteen years. Before that I did another madigra called Patoko. This was a group of men who were masked as women, in nice dresses and high-heeled shoes, and we did a marriage between men and woman on the street. After that we had a troupe called Kanna—we wore blue trousers, white t-shirts, new sandals and scarfs around our waists, and carried brooms with which we swept the streets of Jacmel. I have always found a way of doing Madigra.

- André Ferner (2009)

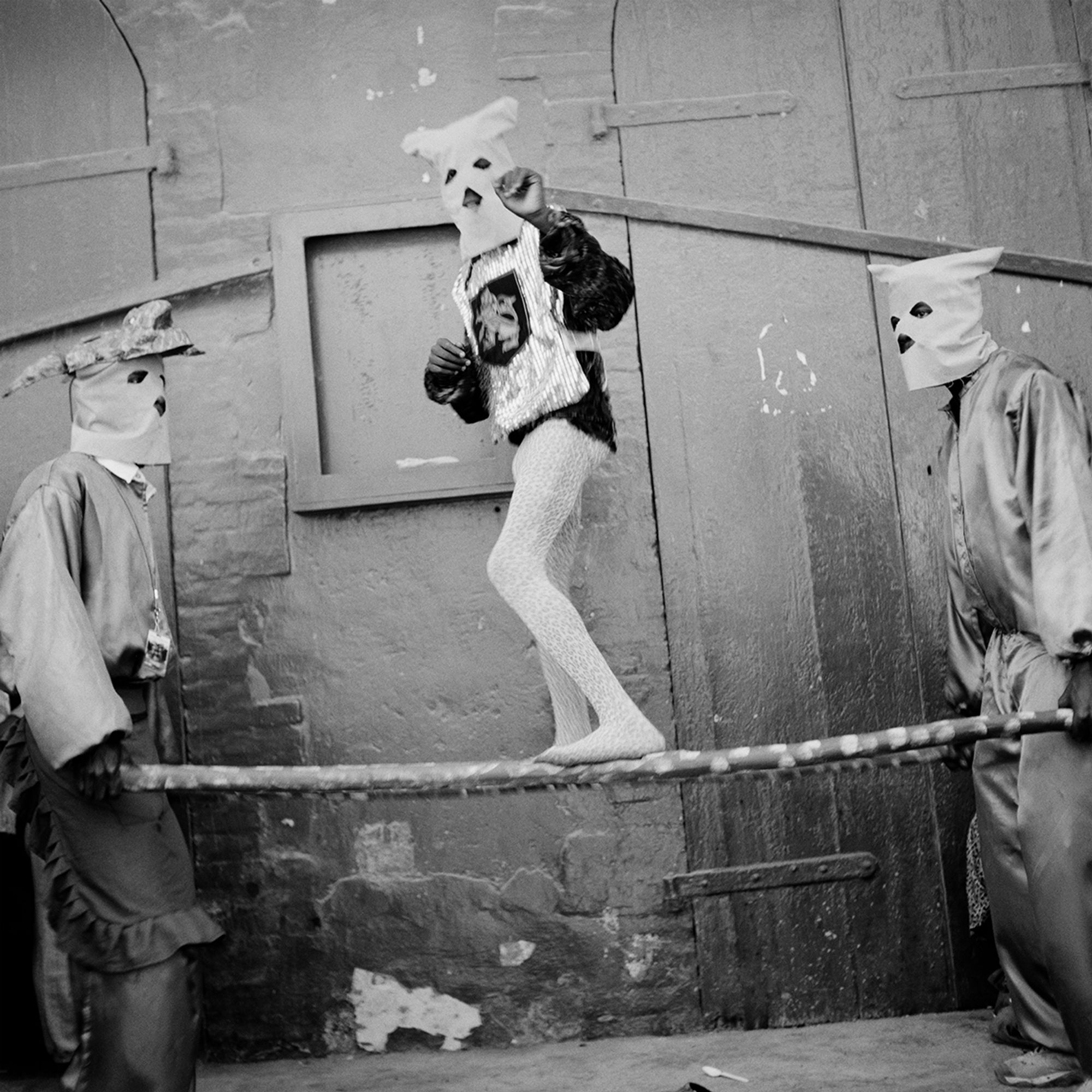

Krapo (Frog)

The frog is a small beast who lives under the water, he lives in the sea, he lives in the rivers and he is free to live as he likes. That’s why people follow him when he dances. Many people in Carnival dance as animals—as horses, birds, lions, frogs. They do all kinds of beasts, they’re free to choose whichever they want. When the music starts the frog dances, the horse dances—everyone dances. This is the song we always sing: Krapo fè kòlè li mouri sen bounda, krapo pa gen bounda ki jan li fè danse (‘If the frog gets angry he will die without his arse, the frog dances because he hasn’t got an arse’). That’s why the disguise for the frog has a big belly, but no arse. I put the mask on and dance with it—no one knows it’s me underneath. They don’t know it’s me when I’m hanging upside down either.

I’ve been doing Krapo for a year now. It’s hard—to join the parade you have to know many moves, dance all the time, and balance on the sticks. I practised every week for a long time before Carnival to get good enough. Some troupes don’t ask for money, and some scare people into handing it over. But we’re a performance troupe—people call us over and offer us a little money to do our dance. They’re happy to pay, but now the prices for everything have gone up. So we sing a new little song too which goes: Krapo pa danse pou de goud (‘Krapo doesn’t dance for two gourdes’). But me, I make the effort and mask and dance on the sticks, but I never get paid.

When I’m older I want to be a tiger and scare everyone. And if I see someone at Carnival making trouble or fighting, I’ll stop them.

- Rousseau Maison (2009)

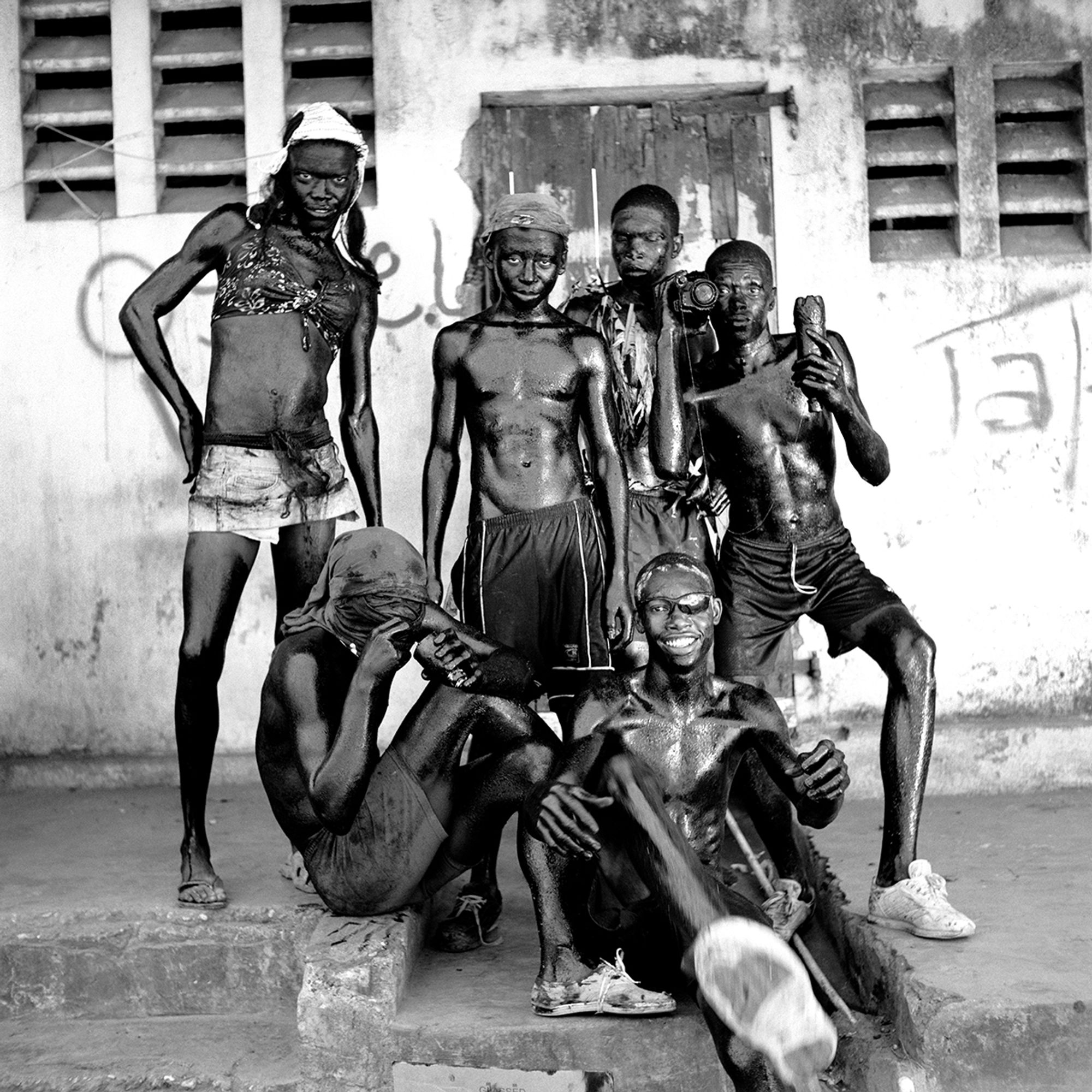

Lanse Kòd (Rope-Throwers)

At Carnival, people like to be scared. We are the scariest. The Zèl Maturin are supposed to be scary, but they’re more scared of us—they worry that they’ll dirty their fancy satin disguises if they touch us. Our disguises are much cheaper to make than many others—no materials, no papier-mâché, just a charcoal-and-syrup mixture.

We are making a statement about slavery and being freed from slavery—it’s a celebration of our independence in 1804. The ropes we carry are the ropes that were used to bind us. We know that slaves never wore horns. But this is about the slave revolt, and we wear the horns to give us more power and to look even more scary. We’re always sullen and menacing. And we never smile. When we take to the streets we stop at the first crossroads and at the blast of my whistle we all start doing push-ups. This is to show that even though the slaves suffer, they’re still very strong. Some of them are so strong that they must wear chains to hold back their massive strength.

I chose to do Lanse Kòd because I know and like the story. When I was child they were always my favourite troupe. But I wanted to do it on a much larger scale. All my friends from the gym, Nabot Power, that I have here in my yard wanted to join. So we have one hundred guys, all fit and strong.

- Salnave Raphaël aka Nabot Power (2002)

Zèl Maturin (Wings of Mathurin)

There have been always Zèl Maturin in Jacmel Carnival, ever since a man called Mathurin Rousse came from abroad with the wings—that’s why they’re called the ‘Wings of Mathurin’. We didn’t invent the story, it came from the old people.

It’s good against evil. The first scene has people with suits, ties, masks and Bibles all kneeling and praying. In the second scene Sen Michèl Arkanj comes down from heaven to give them protection—with him are other angels in pink satin dresses, and a little angel all in blue and white. Then a long procession of Zèl Maturin arrives to steal the angels away, but Sen Michèl kills them with his mighty sword. Then the strongest devil, the red one—myself—arrives. He fights much harder, but at last after a long struggle he’s lying dead with Sen Michèl’s foot on his head. But then along comes the black devil, bigger than the others and wearing chains—his mystic powers so strong that he must be restrained. He carries a skull and presents it to the four points of the compass, and then strikes the red devil three times, reviving him. And all the other devils come back to life too. The black devil, you see, is a Vodou devil—the other devils are mere Christian devils. His powers are greater.

Every year we buy fabric for new disguises—the satin wears out after being washed for a year. We make masks out of this very sticky mud, and decorate them. For the wings I buy planks, saw them up, plane them down. Nail them together, wire them up. Glue on cardboard and paper, add hinges and handles. Then paint them, and attach the tails. It’s the handles that allow you to make them move. It doesn’t take long to learn how to do it—within two rehearsals the trainee’s got it. Obviously, the more experience you have, the better. This year, the new guy might miss something—next year he’ll be good at it. And lately, there are more girls involved—we just have to be careful where we put the straps for the wings, so we don’t squash their breasts.

There’s forty-five people in my team, and I have to pay them all. Nowadays, you can’t get back the money you spend, because there are so many people, and the money you receive is shared between everyone. That isn’t the point though. Even if we don’t get money out of it, we still do Carnival—it’s our culture, and we love it. When you love something you’re obliged to do it well. Every year we bring newness, we create a new piece. But we always have the red and black Zèl Maturin. We’re keeping the tradition going. You know how it goes—someone leaves, someone else takes over. I’ve been doing it forty-eight years now. I was a kid then, and now I’m in charge.

- Ronald Bellevue (2002/2020)

Sen Michèl Arkanj (Archangel Saint Michael)

The Sen Michèl Arkanj madigra is divided into two. One half is on the side of God, and the other on the side of Satan. So on one side you have the pastors, the angels and Sen Michèl Arkanj, and on the other you have the Zèl Maturin, the devils. You can see this in the religious drawings and paintings too. Sen Michèl Arkanj is always killing Satan. The story I do in the street has Sen Michèl standing up with a group of pastors behind him singing hymns and preaching. Then the devils appear, and at first they want to push the pastors around, and then they want to eat them. Sen Michèl is an angel of protection and he has enough power and force to wrest back the pastors from the hands of the devils. When the devils persist in running behind the pastors Sen Michèl must do battle with them. He has a sword in his hand and he uses it to kill them—he has the power to kill all the devils. This is a special tale for Madigra, so although Sen Michèl thinks he has finished killing all the devils, he’s wrong. There’s always one devil that hangs back and hides and doesn’t come face to face with Sen Michèl. That’s because he knows Sen Michèl’s power is stronger than that of any devil. But when Sen Michèl Arkanj turns his back, the last devil resuscitates all the other dead devils by pouring a libation of water on them. He’s able to do this when Sen Michèl isn’t looking.

But this is the only the Jacmel Madigra version—in the real story Sen Michèl Arkanj kills the devils for all eternity. When you do Madigra you always have a message for people. That’s the reason we have the last devil who stays on, hidden, and makes a sacrifice to revive all the other devils and let them live to fight again another day.

Playing Sen Michèl Arkanj would not be my first choice. They gave me the job because Sen Michèl is not supposed to be too tall, or too big. In my troupe I used to be a Zèl Maturin, and I preferred that role. But the guy who played Sen Michèl got really fat, so they chose me to take his place. When I do it in the street I try to make the same skilful movements that the guy before me did.

When you met me last Sunday you photographed me standing still, but next Sunday when you see me in the street we will get to play hard and make all the movements. I can tell you the story, but you have to see the real theatre in the street.

- Jony Aubin (2009) ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast