Daylighting a Brook in the Bronx

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

— Langston Hughes

As I walk the city, I sometimes recite the second line of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” The poem is an amulet. I use it to ward off the scourge of freeways surrounding our house in the Bronx. The Henry Hudson Parkway (NY 9A) that our boys must cross by an ugly pedestrian bridge to get to their public middle school. The Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) that turned back into a river when Hurricane Ida dumped a record seven plus inches of rain. The eight lanes of Broadway (US-9) that divide us from the greenspace of Van Cortlandt Park, where a brook now known as Tibbetts was dammed in the eighteenth century. I haven’t known this ancient little river, one of New York City’s many buried streams. By 1912 its final stretch was strangled into a culvert that led underground to the sewer.

I’ve known roads thick with traffic and loud as hell. Walking over the sewer line along Broadway under the clattering elevated 1 train—check cashing store, pawn shop, smoke shop, puddle, liquor store, dollar store, panhandler, fruit stand, puddle, laundromat, bodega, barbershop—you wouldn’t know that ours is a riparian habitat. Except, of course, for the puddles that remain after it rains. These days when it rains, it pours as if the very sky was torn. A puddle persists in a dip in the road directly in front of our house. The puddle has an attitude like, “Yo! I belong here. Do you?” A nineteenth-century map indicates that our house sits on the historic pathway of Tibbetts Brook. The brook’s absence seems sad and wrong. I live where something significant was intentionally vanished. Since discovering this, I’ve been following the ongoing restorative effort to “daylight” or unbury its water.

Daylighting Tibbetts Brook is one of the city’s most ambitious green infrastructure projects to date. It will cost $133 million to restore the waterway along a new route that won’t disturb the neighborhood’s structures, including our house. That sounds like a lot of money, but it’s a bargain compared to the high price of sewer and stormwater overflows when cloudbursts drop their heavy payloads. On dry days, four to five million gallons of freshwater flow from the brook into the sewer, ushering our filth and concentrated street runoff down to the Wards Island wastewater treatment plant. But when we get rain bombs, the volume of water is way too much for that system to process and spills unfiltered into the Harlem River, further contaminating the ecosystem, sickening all it touches. Daylighting will abate combined sewage overflow, extend greenspace, absorb heat, and relieve chronic flooding in our area’s janky, archaic drainage system, in an act of climate mitigation and as a community effort to solve a mess caused by old crimes.

When the crimes that got us into this crisis feel too much to bear and this endangered place itself—redlined, polluted, haunted—feels nearly unlivable, I recall what Mr. Rogers once told his television neighbors. “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”

*

My first encounter with the daylighting project was in the spring of 2023, when I went on a site visit with the Tibbetts Advisory Group, which included folks from the city’s Departments of Environmental Protection (DEP) and Parks & Recreation, the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance, the local community board, and Rebuild by Design, an organization that collaborates on climate resilience. The helpers. Some of them had been advocating for recovering Tibbetts Brook since the nineties when I was about as young as our children are now. We met at the terminus of a dead-end street, but there was a feeling of excitement and possibility in the air, like at the bottom of the ninth when the Yankees are about to win. I’d gone on walks of the city before, to reckon with climate change, sometimes with a companion and sometimes alone, but never in so organized a fashion, nor in a group dedicated to a solution. I felt cautiously optimistic. A representative from Bronx Climate Justice North reminded us that this was an environmental justice community with co-morbid social justice issues, that decades of disinvestment and poor urban planning had fractured and isolated the borough—which suffers the worst air and highest rates of asthma in the city—and that the Bronx was nearly destroyed by highways. Daylighting was a way for the city to do the right thing.

Before crossing a chain link fence to survey the site, we went over the plans. About a mile of the brook would be brought back above ground from Van Cortlandt Park South to West 230th Street. It would flow alongside a newly built greenway with a ten-foot-wide bike and pedestrian path, beautified with native plants and public art under the overpasses. I was grateful to learn there would be several direct points of entry to the greenway from Broadway. My boys would no longer have to cross the busy interstate to bike to the park. But the brook would need to be piped back underground to accommodate a section of railroad tracks owned by the MTA, which are dedicated for garbage transfer and Metro-North’s Hudson line. Meaning, the residents of the NYCHA projects in that industrialized area of Marble Hill (which in 2018 had the city’s highest report of street flooding complaints to 311) wouldn’t get easy access to the greenway at all, raising the question: by whom and for whom was this venture?

Imperfect as it was, the daylighting plan was progressing. The final roadblock was the steep price of the land needed to reroute the brook above-ground. At this point in the story, the city was trying to cut a deal but the freight company that owned the real estate was acting like a crook.

We walked for several blocks along that contested property: the narrow corridor of a former railroad wedged between the Major Deegan Expressway and a string of strip malls and big box stores. Petco. Staples. Cubesmart. Target. Parking lot after parking lot over what was once marshland. Here and there the route remained marshy and thick with reeds. I noticed an abandoned shopping cart, the puddles stained red with iron oxide, the pawprints of a raccoon in the mud. It was hard to hear each other speak over the ceaseless roar of traffic. The acoustics were as god-awful as the air. All that separated us from the highway and its toxic fumes was a concrete guardrail, in some places only three feet high. I took pictures of graffiti and busted refrigerators strewn behind businesses whose basements regularly flood.

A landscape architect who lived elsewhere yelled something about how lucky we were to witness this place before it became an attraction, how when the Deegan was cut through here to continue I-87 and the train and sewer were built—and the chain stores came—each one had an easement. How easements overlap easements, so we wind up with waste space. How we were now walking somewhere between nature and not nature. How when this no-man’s-land gets remade as a public park, rail to trail—like Manhattan’s beloved Highline—new people would visit, revitalizing businesses in the vicinity. How wildlife and pollinators would share the habitat, too—the hope being to keep it wild, to enjoy the land along with other living things.

I had so many ethical questions without easy answers. It felt uncouth to ask them of a dream thirty years in the making. In any case, I doubted I could have been heard above the Deegan’s speeding cars and trucks. Unlike when walking the Highline, we weren’t lifted above the city’s bustle, but ambling directly beside the worst of its blight. Could it ever be pleasant here? Difficult to picture. Even with the brook resurrected, there would still be the sound of the road.

What does it mean to be a good steward? A good ancestor? What ought reparation, resilience, and restoration look like given the scale of the crisis at hand? The water never really went away. It still remembers where it used to be. Long ago, the Munsee Lenape called the brook Mosholu, meaning “small” or “smooth” stones. Mosholu. I gathered several small, smooth stones in my pockets along the walk, from among the duckweed, trash, and muck. I later made a ring of them around the little shadblow tree I planted in our backyard in memory of my father. At first it was just a twig but has recently begun to grow. Eventually it will be underwater, along with our house.

As if pointing to my failure of imagination, someone from the DEP much younger than myself shouted that in due time the vehicles would all be electric, and consequently quieter. The working group went on pointing out the future features of the linear park. For example, where benches in the style of those at the 1964 World’s Fair and native trees would go: red maple, sweet gum, river birch. I wondered: how else might the park change the neighborhood? Will it invite gentrification? Will it grow too expensive to live here? Despite the ecological and economic benefits, will anyone suffer? Can daylighting outpace inundation, or will it be rendered moot by water tables that rise with the sea? If flooding catastrophes continue, what then? Would government funds be better spent moving the most disadvantaged among us out of the watershed to higher ground? Has anyone asked for the brook’s consent? Whose help is sanctioned when it comes to healing the land, and whose is rebuked?

I couldn’t help thinking of Alicia Grullón, an artist acquaintance and CUNY colleague who lives in the house she grew up in just a stone’s throw away in Kingsbridge Heights, on the east side of the Deegan. I’d asked her to join me on this daylighting walk and she’d politely declined, citing a dispute with park authorities that left her wary and somewhat bitter. During the pandemic, she and a band of other local, activist cis women and gender-nonbinary people of color in the North Bronx Collective devoted themselves to cleaning up Tibbett’s Tail, an overlooked park running between 234th and 238th Streets. It lays parallel to (yet invisible from) where I stood with the Tibbetts Advisory Group, imagining the daylit brook as the crown jewel of a park that does not yet exist. Tibbett’s Tail is an unwelcoming dumping ground on the wrong side of the road. It has no benches or trails and, being entirely inaccessible to the public, is overgrown with brush.

Sensitive to the disproportionate blow by COVID-19 to the Bronx, where an overflow of dead was buried in a potter’s field, Alicia and the collective rolled up their sleeves to make Tibbets Tail a place for respite. Committed to mutual aid, land liberation, spiritual uplift, and the belief that parks are for the people, they worked hard to remediate its lead-degraded soil and nurture its medicinal flora. They partnered with a local church to use the park as a meal distribution site for the hungry. They also passed out face masks there, planned programs on healthy eating and composting, communicated their grassroots efforts to the proper advisors, including the Bronx Parks Commissioner’s office. Due to their good work, they even received funding funneled through the New York Restoration Project with which they installed raised garden beds to grow vegetables.

Helpers, I tell you. Within a few months the members of the collective succeeded in transforming the abandoned park into a vital community hub, only to find themselves shut out—the gate was literally padlocked by Parks, citing unspecific safety hazards. Getting locked out must have felt like a slap in the face. To the collective it reflected a larger pattern of intimidation, surveillance, and neglect in the city’s poor Black and brown neighborhoods, so often deficient of green. And now, having exiled those helpers, the city was powering up to bankroll this sexier thing.

Some workers in white coveralls were painting over graffiti on the back wall of BJ’s Wholesale Club, making a blank canvas for someone to tag again tomorrow—as true a metaphor for impermanence as ever there was. We are at an inflection point. A critical time for reimagining, reckoning, repair. There was a labor struggle here back when BJ’s was the Stella D’Oro Cookie factory; before that, a struggle between the Redcoats and the Patriots during the American Revolutionary War; a struggle when Dutch colonizers grabbed Indigenous people’s land. Mosholu is now the name of a parkway in the tangled road network constructed under arterial coordinator Robert Moses. Tibbetts is a bastard name for a bastardized brook, a misspelling of the last name of colonial settler George Tippett, whose loyalist descendants got kicked out of New York. It’s remarkable how many spots in the neighborhood are misnamed after this guy. The brook’s revival is the nation’s highest profile case of daylighting in a major city to date. As one neighbor said, “We got bragging rights in the Bronx.” Many of us look forward to some recovery of the watershed. At the same time, the brook is calling us to look back.

*

Such a poetic name for a feat of engineering: “daylighting.” It’s happening or has happened in cities all over the country and across the world. Berkeley, Boston, Detroit, St. Louis, Paris, Zurich, Sheffield, Manchester, Madrid. Adam Broadhead, senior scientist at the sustainable development firm Arup, has been researching daylighting projects worldwide. He wrote to me about the terms for daylighting in other languages. The Swiss refer to it as the sensible bachkonzept, or “stream concept.” In German, it’s the practical offenlegung, or “deculverting,” also regularly used in Great Britain. In French, the more romantic réouverture, “re-opening,” or remise à l’air, “returning to the open” of “disappeared waterways,” rivières disparu. Writer Anton Hur, who translates Korean literature into English, tells me that “restoration” is the best match of the Korean term, 복원, used for the daylighting of the Cheonggyecheon in Seoul.

Most daylighting involves restoring some or all of a previously covered river, stream, or stormwater drainage to a more natural state, but there are other ways of daylighting. Architectural restoration exposes the stream to open air while confining its channel within concrete walls. Cultural restoration celebrates a buried stream through markers or public art created to inform people of the stream’s original route, although the stream remains hidden. Now that NYC has finally cinched the land deal to unearth Tibbetts Brook, paying more than $11 million for the strip we walked, daylighting is expected to begin in late 2025. But it’s already been happening culturally for years, most prominently through a constellation of artist and designer-led initiatives through City as Living Laboratory (CALL), a nonprofit that seeks to make sustainability more tangible.

In Visions of Tibbetts Brook, a conceptual artist worked with local school kids to craft collages about the future greenway. A pair of artists led 100 volunteers to embroider the Tibbetts Estuary Tapestry, a quilt that re-envisioned our neighborhood’s poor planning with green roofs, bioswales of vegetated ditches, and rain gardens meant to heal the paved over habitat. In Estuary Tattoos, another artist mapped the history of Tibbetts Brook and its wetlands on the bodies of locals, making people into works of art by painting the pre-urbanized waterway on their skin. I talked to Bronx-based artist Dennis RedMoon Darkeem, of Creek, Seminole, and African American background, whose great grandparents healed themselves by planting certain herbs at certain seasons. For his upcoming public art project on the daylighting of the brook, he imagines weaving mugwort that grows invasively in Van Cortlandt Park into a massive blanket and hanging it from the rusty remains of an old railway station to create a sound barrier, “for protection.”

I appreciate how initiatives like these offer an expansive response to catastrophe, a way to gather, and even a sense of hope. It’s not just the architecture of the daylighting project that interests me, the restitching at the scale of infrastructure, or the civic muscle behind the job, but the metaphysics of the exhumation. Daylighting feels like a cause for ceremony, a chance to pay respect to the body of the ghost river that flows unseen under our feet. Better yet, to imagine the perspective of the brook.

What is the memory of water? Is this captive chapter just a blip in the long life of the brook? Or might the brook be angry, like a poltergeist deranged by degradation, indignity, and concealment? I mean, does the brook hold a grudge? Has the brook been dreaming of freedom, attempting repeated escape? What are the brook’s rights? I don’t wish to anthropomorphize, but how do we match our repair work to the level of harm that’s been done, not to mention, to the soul of the brook?

Quoted in a recent article on daylighting for Orion, the deputy director of the Lenape Center in New York, Hadrien Coumans, who is an adopted member of the White Turkey-Fugate family of New York’s first peoples, said, “I don’t think that any living person today has a real understanding of what this original ecosystem was. For many Lenape, Coumans said, “each of these streams and rivers have a spirit, and the spirit must be recognized, acknowledged, given thanks to, and offered that kind of consideration, in its place, for life to thrive. Daylighting efforts are one element in a whole of what would be the restoration of an original ecosystem.”

If anyone today has an inkling of that unknowable past, it’s Eric Sanderson, senior conservation ecologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society, based at the Bronx Zoo. His landmark project, Mannahatta, has attempted to convey what NYC was like 400 years ago. Sanderson understands the potential of the watershed from a place of curiosity about how it once functioned. According to an analysis of the West Bronx he spearheaded, this part of the city retains approximately 16% of its original rivers and streams. Of the former 307 hectares of wetlands in the study area, less than 1% remain. A staggering loss. “If you look at the city today, it’s hard to imagine it could be anything else,” Sanderson said in a 2017 video on CALL’s website about the daylighting of Tibbetts Brook. “In the city, we’re so used to how people made the city. How did the soil get here? People didn’t make the soil. Nature made the soil. It took thousands of years for the soil to get here…If we understand the historical ecology then that gives us some metrics of what sustainable ecology would be.” Sanderson’s work helps reconstruct the long life of this little river that I am coming to know. To paraphrase:

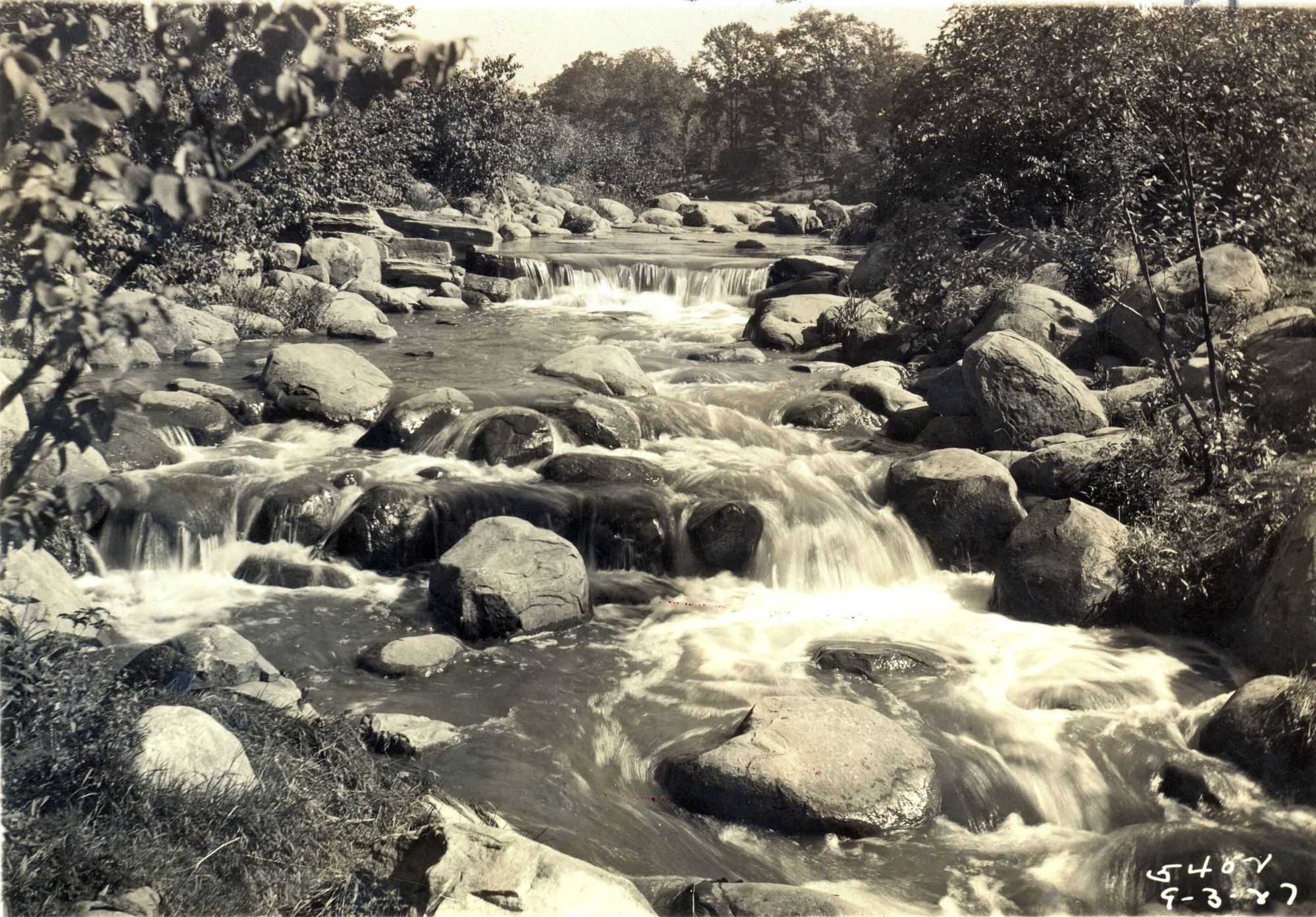

For millennia the brook babbled and tumbled down the valley carved by a glacier. The brook ran, swelling with rain, to the sea. In time, the climate warmed. The sea rose to meet the freshwater brook, filling the lower valley on the high tide and forming a brackish sward of salt marsh. The lower brook began breathing in two directions. In on the flood tide. Out on the ebb. The upper brook meandered in curves that changed color when the teeming algae was struck in the changing light and when the water mirrored the changing sky. Blue. Green. Gray. Brown. Black. Trout swam in that part of the brook’s body, and shad. The real people came to live along the bountiful banks of the brook and by the mouth at the edge of the marsh. They settled on a small sandy island, a flat place, under the flightpath of turkeys, within earshot of howling wolves. They made trails up the bluff to the west where they shaped the land with fire. They understood that some spirits, such as rivers, have bodies that long outlast our own.

Much later, new people came with weird ways. They built dams, planted crops, wrote treaties, owned slaves. In their grab for land, they swindled, murdered, massacred, and chased the real people west. (To write such erasure in one breathless sentence feels craven, I admit.) Along with their agriculture, the new people brought industry. They built homes and streets and trolley lines. They floated farm produce to market along the brook in summer and in winter ice-skated on its frozen skin. Then came the train. In its tracks the brook grew despoiled. Mosquitoes bred. The new people feared malaria. The brook’s dirtied water issued their trash and waste downstream. When it rained, they complained of streamwaters flooding what they thought were their properties. In their view, the brook was an impediment to progress, a health hazard, a thing to backfill for capital gain. (Though why should I whine / Whine that the crime was other than mine? wrote Gwendolyn Brooks in “The Mother.”) The city increased its grid. More new people, more buildings. More buildings, more land. More land, more new people. These people. My God, did they bungle the hydrology. They preferred their land dry, and hardscaped the watershed to spread and build, driving the brook underground. For over a century, it has remained hidden, in the dark.

Now, it’s being brought back to light. Sanderson again:

If we could make our city work like it did when it was a forest and a wetland, and still have all the people, well that would be the big win. Right? We’re so ambitious for its economy and architecture and culture and science, but we think, there has to be a cost, and that cost has to be borne by the environment. We’re almost naturally pessimistic about our ability to make the environment better. I don’t get that. Why can’t we be as optimistic, positive, and affirmative about how great the environment can be? This is the work of artists to activate our imaginations … Science itself doesn’t get you there.

*

My second encounter with the daylighting of Tibbetts Brook was in January, 2024, at a storefront gallery uphill from our house. The occasion was the opening reception of an exhibition by local landscape painter Noel Hefele. The small space was packed. Sushi was served. I recognized Noel from the walk the previous spring. When I told Noel it felt like the brook was working to bring people together, he nodded. A humble guy with a philosophical air, he’s attuned to the brook’s vibrations. He spoke softly but with purpose about the fifteen canvases hanging on the wall: “Artists help us learn how to listen to, understand, and live within our landscapes.” The paintings were charmingly naïve. Noel hadn’t used watercolor in 20 years before painting this series, Daylighting Tibbetts En Plein Air, but the medium matched the content. Since we were inviting water back into our neighborhood, he felt it necessary to think in watercolor. The day he planned to begin his project, which was supported by a City Artistscorps grant, was the day Hurricane Ida struck, inundating the Deegan. Noel saw that the highway was also a river, but of oil. It struck him, as the water rose, that the brook was both returning and had never left.

For a season, Noel painted the water’s path. It was an astonishing feeling, looking into the prelapsarian landscape while walking through its current form. He came across a puddle on the asphalt where Tibbetts Avenue crossed 230th Street, which transformed for him into a remnant of the historic brook, “like the traces of graphite that remain when you try to erase a drawing.” People were curious about him. A landscape painter standing with an easel by the highway is an unusual sight. He had countless conversations with community members he never would have talked to otherwise. He’d prepared a bilingual handout—in English and Spanish—about the daylighting proposal to pass out to residents, assuming the idea of the river’s return might not be common knowledge. A lot of folks said, “I’ll believe it when I see it.” Some of them assessed his artwork or shared art of their own on their way to the bus, to work, to pick up the kids.

“Daylighting a buried stream begins in the public imagination,” Noel said, convinced that “the project must weave into the local fabric and not just cut through it in a sharp line.” Given that the floodwaters are coming, he wondered if our community would be proactive or ultimately reactive. Could painting have any impact on, or contribution to, this critical moment? Only after he finished the series did he realize that he was already part of the moment by deciding to paint it, “as if enlisted by the water itself.” In other words, painting was not a catalyst but proof of a change already afoot.

“A watershed is not just the path of the water, but it is the culture, the people, and the attendant ecosystems as well,” Noel observed. “The water is rising in the minds of those who understand we must invite it back.” He was still practicing how to listen to the water. But, I wanted to know, how does one hear it through all the noise?

*

My third encounter with daylighting had this very question in mind. The Buried Brook, an augmented reality soundwalk along Tibbett Avenue, was created by Kamala Sankaram, a composer of contemporary opera and experimental music who previously wrote a ten-hour opera for the trees of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. For this new artwork, sponsored by CALL, she’d designed a phone app that guides listeners to walk where the brook used to flow, listening to sounds of music and water along the way in concert with their phone’s geolocation data.

In May, 2024, the community was invited to hear Kamala talk about her project before undertaking the soundwalk. About 20 of us showed up, including Noel, Dennis, some birdwatchers, and several senior citizens. We gathered in Van Cortlandt Park, at the weir at the edge of the lake where the dammed brook drops dramatically down into the sewer. The chokepoint had a spectral feeling and stank of sulfur. The lake was recently renamed Hester and Piero’s Mill Pond after the enslaved miller and his wife who worked for the Van Cortlandts, a wealthy landowning family who ran a wheat plantation here before it became the park. A hundred steps away, in the direction of the tennis courts, a sign marks the site of an African burial ground. Dennis told me that before the highways sliced through the land, the gravesite used to be much bigger than it is now. “How much that’s now roads is actually ancestors?” he pondered.

Kamala had a UFO on her t-shirt and a fig leaf tattooed on her arm. She explained how to use the app as a guide to the past. Along the soundwalk, we could use a slider on our phone screens to fade away the neighborhood as we know it via Google Maps, and bring into focus a historic map from 1892 showing the brook running freely. The soundwalk urged us to notice the old topography as well as to listen. A few of the senior citizens had trouble with the technology. But there was another element planned that they could participate in: a creative writing exercise. Each of us was handed a tiny recycled-paper notebook and a pencil. Kamala then introduced us to Raymond Pultinas, a retired high school English teacher who now works for the James Baldwin Outdoor Learning Center operating a farmer’s market off Mosholu Parkway South. The helpers are everywhere, if you look for them.

What sounds do we normally tune out and ignore? What’s the quietest sound? The loudest? Ray asked. With our eyes closed and our ears open we meditated near the skatepark where the brook used to run. I was acutely aware of the noise pollution. I heard the highway, a motorcycle, the screeching 1 train, a pounding jackhammer, and the drone of an airplane. Breathe through your nose. Listen harder. Under that racket, some more pleasant sounds: the jingle from a Mr. Softee ice cream truck, the bright horns of salsa from somebody’s boombox, a basketball being dribbled on a nearby court. Listen for sounds that might have been here prior to all this development. I heard the calls of a cardinal, a red-winged blackbird, a virio, and a yellow-bellied sapsucker.

Ray had us open our eyes, write down our observations, and consider not only that our relationship with the land could be a conscious choice, but that the river was consciously determining its own path. Many places look the same owing to corporatization, Ray said. We could be anywhere. But there are particular things one can do in one’s local environment that one can do nowhere else. What do you notice? Bottlecaps for Corona Xtra and bright circles of foil confetti pounded into the dirt. A squirrel brazenly eating a french fry. Ray asked us to sit in the grass and reflect on how we’re entering a new era. What words could we give to this unfolding? What does daylighting really mean?

People shared their definitions. To reveal. To illuminate. To bring to the surface. To expose. To bring to light. A compound, the word pairs a state of affairs and action, like landscape, timekeeper, nightlife, sunset. Ray wanted us to get out of the human way of thinking. What will daylighting mean to other creatures? A worm might experience it as “moisture-gift,” a fish, “path-making,” or a coyote, “territory-growing.” An old man wearing an “I LOVE NY” baseball cap and a camera around his neck objected that for some creatures adapted to the way it is now, daylighting would be an intrusion, like the Cross Bronx Expressway that displaced his parents. “Don’t be a putz,” said his wife. “On the whole, it has to be better to bring nature back.”

I parted from the group at the park’s 240th Street entrance to follow the brook’s original course. Please use caution and pay attention to your surroundings, warned the Buried Brook app. Nevertheless, I blocked out the city’s violent overload, and listened to the water. I crossed Broadway and turned up the volume on Kamala’s soundwalk as high as it would go. Kamala had gathered many sounds: field recordings of birds in the park; using a hydrophone underwater, the lake; Hindustani ragas associated with rain; and a song sung in Munsee gifted by Nicole Pecore and Ja’Ni’Ya’Ku’Ha Webster, of Mohican, Munsee, Oneida, and Menominee Nation (with respect to the original Lenape inhabitants of this land and their deep connection to the brook, Mosholu). It gurgled in my ears. Rounding out the soundscape were an mbira, a xylophone, a saxophone, an accordion, and a sitar, which kicked in by the jeep dealership.

I walked west toward Tibbett Avenue in the direction of our house, consulting the map of the past. I followed the blue line. Its squiggle contradicted the grid. I stayed on the sidewalk. If I allowed my body to meander like the brook, I risked trespassing, or getting hit by a car. But my mind could wander with Kamala’s composition. I passed Gaelic Park, the playing field of Manhattan College. The music relaxed me. My shoulders softened. My pace slowed. So did my breath. At Tibbett, I turned left, tracing the brook south. I can’t say how I knew that the song in Munsee was an ode giving thanks to the water, nor that the spoken text that started by the physical plant at the corner of 239th Street was admonishing us to respect the water, but I did. Water is the life river of our Mother Earth. Water is Life. That is what the women sang. I straightened my posture, to dignify the brook.

I passed a six-story cooperative apartment building called The Brookside. The wind was blessing my face, like water. The same flier was stapled to every telephone pole I passed: Expressway Moving. $190. 2 hours, 2 helpers. My breath deepened. The water gushed. I nearly felt it lapping at my ankles. As I approached our corner at 236th Street, I was overcome by a feeling of loss. I could glimpse the brook now, as through a parted veil. Pulled by the current, I waded down Tibbett backward in time, past the trash-strewn catch basin and station of Citibikes by the rubbled lot of the burned down drug house at 234th Street, past the often flooded construction site for a new charter school at 232nd Street, past the Tibbett Medical office offering pain management, past the Bx7 bus stop at 231st Street and the Tibbett Diner, all the way to a DEAD END sign at the intersection of 230th Street where the brook used to empty out into the Spuytin Duyvil Creek in the old days, before the wetland was paved over. I stood in that spot for a long time, listening to the water with my eyes closed. I might have looked crazy. “I’ve known rivers,” I said. When I reopened my eyes, the U-Haul Storage facility, the TD Bank, the car wash, and the BP gas station were still there. The price of gas was $3.77 a gallon. I touched my face, and found it wet. ♦

This essay was sponsored, in part, by Social Practice CUNY.

Subscribe to Broadcast