Zadie Smith: Flowering Under Stress

It’s strange to remember the moment you first heard the word “pandemic.” I mean, now that the word is as familiar to us as our own names. I remember it as a falling feeling, one of profound unreality, like the tumble Alice takes down that rabbit hole. Just when you thought you couldn’t fall any further, you kept going. Most of us just fell. But if you were like Alice—or like Ana Prvački—after a while, you were able not only to fall but to notice things as you fell. Your own body. The things around you. Words and their meanings. The long, bewitching ears of the white rabbit himself!

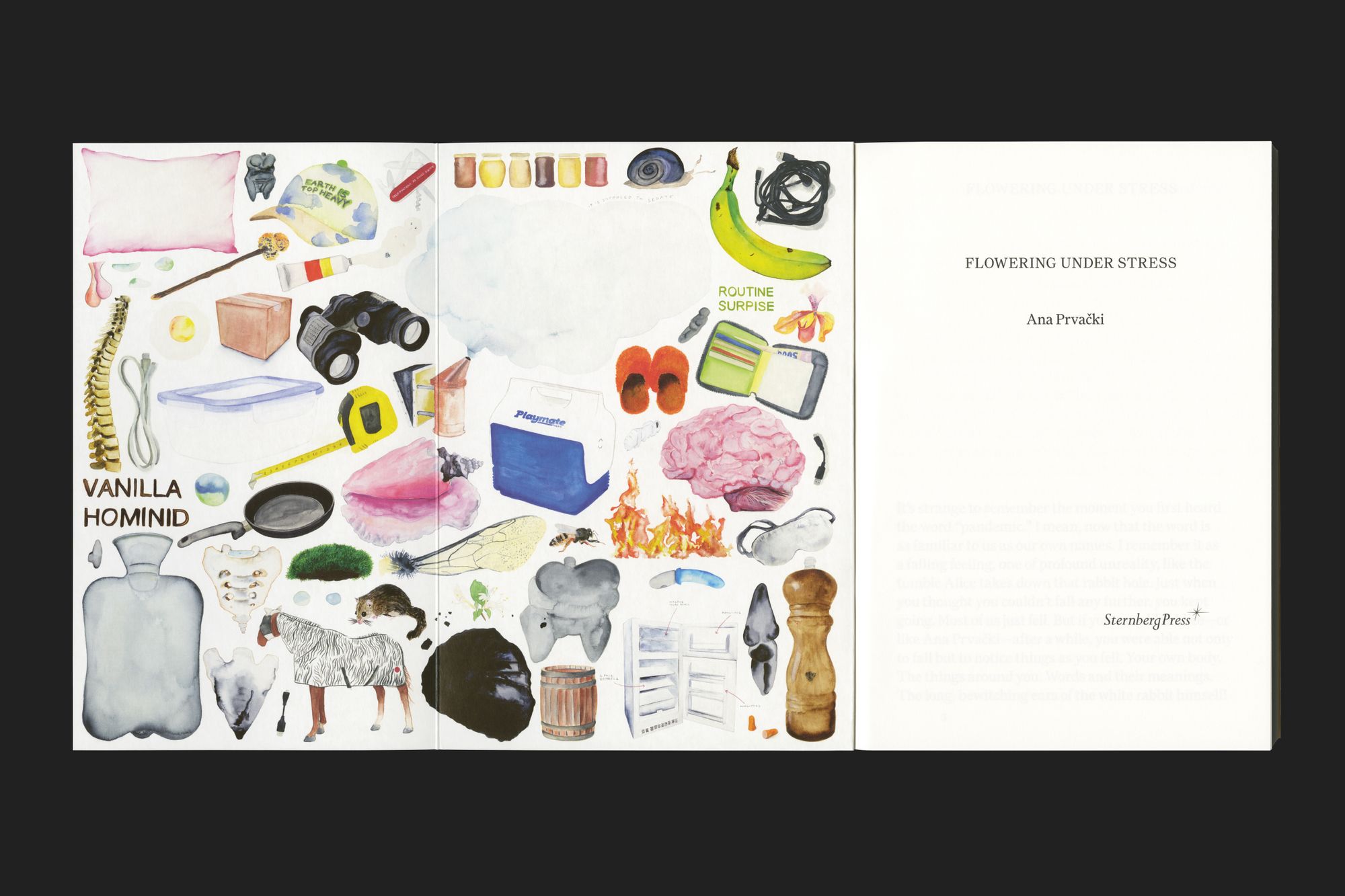

During the pandemic, objects shimmered and vibrated, mostly because in your fugue state, you were often to be found sitting around just staring at them, paying them more attention than you ever had in your life. You’d never known your home so intimately, nor been so familiar with the various items inside it. Frying pan. Slippers. Pillow. Bath. The borderline between the animate and inanimate became indistinct, like Albrecht Dürer’s famous squirming pillows. Things spoke to you. And if you happened to be living alone, well, more often than not, you spoke back.

With less to look at, we looked intently. And when you went outside on your regulation walk, if there was sun, then it was the sunniest sun ever seen, and if there was rain, every drop was outlined and specific. It was possible to get to the point where you could identify different types of dew. The particular became the universal. A squirrel became “wildlife.” A pine tree became “nature.” The horizon became very good for your nervous system. Also: the sky. Also: any view of mountains or hills. Of course, you were terribly nervous and all the time. And when you weren’t nervous, you were: nauseous, anxious, angry, fearful, sad, and desperate. You languished!

Meanwhile, at the kitchen table, “Hybrid learning” led to hybrid-children who could pretend to be attending their Zoom lessons while simultaneously texting, TikToking, or making a study of the acrobatic squirrel walking the tightrope of the laundry line. The hybrid-children’s parents swore to Jeff Bezos and upon all things unholy that they were never, ever going to use Amazon again—but then you went and used Amazon again, didn’t you? Yes, you did. Me too. If only because the arrival of a box could break up a day:

Before box

After box

You opened the door in dressing gown and slippers and realized that you had just ordered a real living person to come to your door in the middle of a pandemic to bring you something you really didn’t need, wrapped up in packaging that will last forever. Then you swore never to do it again. The earth is top-heavy because of people like us.

Nature was good for our nervous systems, but even in nature, there were few places for the mind to rest. We were having hell for breakfast, every day, and then more hell for lunch and dinner, too, and if you stepped outside to take some pleasure in nature—in a horizon or a hill or the shoreline or the sky itself—a moment later you remembered that nature, too, had a virus, a virus called humans, and it was because of all us that the bees were dying and the earth was top-heavy, for far too many of us at the top were hoarding resources while the bottom half suffered. We tried to burn the shame and sadness of all this like calories, undertaking many new hobbies and fitness goals and community projects, although more often, we languished and we marinated. Imaginary scenarios were constantly on our minds, and the only thing we could imagine was apocalypse.

But! The mind is dexterous and can make of anything a metaphor, make of anything a simile. A woman can see herself in the curves of a pepper grinder or the angular gestures of a coffee pot. A woman might lose all sense of her own citified modern reality, seeing herself in a bowl of primal ooze or in the ancient nobbled fertility statues archaeologists sometimes dig out of the earth. Some days were for making art. Others for hiding under a duvet and despairing. But whatever we did, we knew we were like juvenile swans, that is, in a period of radical becoming. Nobody knew what they would be like at the end of it all. (If it ever ended. If it has ended.) But everybody knew they would never be the same again. I wish I’d had Ana Prvački’s exquisite series of existential watercolors with me during it all, when my nervous system was utterly broken and I didn’t know which way was up... in that long, dark, seemingly bottomless hole. Whispering in my ear like a homeopathic sea shell:

You are going to be ok

This too shall pass

I am here for you

We are all in this together ♦

This text has been excerpted from its form in the publication Flowering Under Stress, by Ana Prvački with an essay by Zadie Smith, published by Sternberg Press and designed by Wolfe Hall.

Subscribe to Broadcast